Like every year, 2025 had a lot of games that I missed. With things quiet, I was drawn to Wanderstop, an indie game from the creator of The Stanley Parable and The Beginner’s Guide. That’s a claim that will raise some eyebrows, so perhaps it’s best to get something clear: if you’re expecting the creator’s usual bait-and-switch twist, there isn’t one. Wanderstop really is just about making tea and slowing down.

The starring role and player protagonist is Alta, a woman who has dedicated her entire life to her obsession with being the very best fighter in the world. She trains every day, pushing herself mentally and physically to the limits, leading to a multi-year winning streak.

Available On: PS5, Xbox Series S/X, PC

Reviewed On: PS5

Developed By: Ivy Road

Published By: Annapurna Interactive

You can’t remain undefeated forever, though, and Alta eventually loses a fight. And then another. And another. Unsure of why she’s suddenly unable to win, Alta leaves to find Master Winters, the only person she believes can help her regain her strength. But as she runs and runs through the forest, she grows tired, exhaustion settling into her bones like an unwelcome houseguest taking up residence, an unfamiliar feeling for someone who thrives on pushing the limits. And then she drops her sword and collapses.

That’s where the strange Boro and his odd teashop enter the story. Boro finds Alta passed out in the woods, rescues her and scoops up the sword. Once awake, Alta discovers she still cannot pick up her sword. To everyone else, it weighs very little, but to her, it is immovable. What is she without her sword? Without the ability to fight? Without being able to train every single day?

Boro suggests she needs to rest, and asks if she would like to help run the teashop for a while. Confused, she seeks direction and tasks: what would she be doing? And gentle Boro simply tells her to do whatever she wants. She can serve customers, sweep the leaves, gather the ingredients, hang photos on the wall or do nothing at all. He simply wishes for her to take the time she needs. Alta, though, struggles to understand this concept and even seems to view the whole thing as beneath her at first.

Thematically, we’re dealing with a lot of shit, man. Wanderstop is about what happens when you devote everything you are to a singular goal, and that goal slips out of reach. It’s about burnout, exhaustion, and the uneasy battle between productivity and rest. It’s about how the same drive that pushes you toward greatness can also grind you into the dirt.

Wanderstop captures all of this beautifully, and it does so in a few key ways. The first is through Alta herself, a somewhat unlikeable character for the first while, because her drive to push herself and her self-loathing at being unable to wield her beloved sword make her stand-offish and rude. But throughout the game, and aided by Boro’s gentle companship, Alta begins to open up, although the small dialogue choices you’re offered let you keep Alta a little more closed off, if you’d like.

Regardless of the small choices you make, Alta shifts to a person who is easy to empathise with, whether it’s because you also struggle with relaxing without seeing it as a chore, or because you’ve also crashed hard due to a singular obsession. The downside is that if you’ve never personally experienced anything like this, Wanderstop as a whole might fail to resonate properly. You may finish the game and find yourself asking what it was about, what the lesson was, what the point of it all was.

As for Boro, he’s a gentle giant of a man, full of patience and understanding. I love how his dialogue is written. Voice acting is reserved purely for a few moments, such as when you take a moment to sit on a bench with a cup of tea, so everything is handled via text, and the writers do a superb job at giving Boro a unique style of speaking. I could instantly hear him in my mind.

Another way the game delivers is through its atmosphere. There’s a palpable cosiness to the game, even while it is, in some ways, taking a few cheeky potshots at the rash of cosy games and books that have popped up. Although the graphics are simplistic, the use of colours makes this a lovely game to eyeball.

To me, the game smartly does a lot with very little in terms of storytelling. Every piece of dialogue and character interaction is kept as tight as possible, perhaps to the game’s detriment, because I’ve seen a few user reviews saying that for a “narrative-driven” game, there’s not a lot of story, or resolution. These are very real criticisms. But to me, indicate that the reviewer may have bounced off the themes, leaving them seeking a more typical storytelling method, whereas someone who resonates with it – like myself – will find it just right.

All of this mental muddiness is solved in the most British way possible: a cup of tea. It’s our go-to method for dealing with anything. Has a friend come bursting into your house, clearly upset? Go make a cuppa. Arm been cut off? Ach, a nice cup of tea will help you feel better. Has your entire family been liquified and your dog kidnapped by canine-eating aliens? Tea. Tea will solve it. Or, more precisely, the act of making tea will buy me a few precious minutes before I have to deal with your shit.

Customers will venture into the teashop from time to time, bringing with them requests for different flavours of tea. Some are specific about exactly what they want and how to make it, others might not be so sure, leaving it you to figure out what they need. Whatever it might be, there’s no rush to brew the tea – they’re happy to wait as long as is needed.

The act of making tea means using Boro’s giant custom brewing apparatus. This glass tower is so tall that you need a ladder to get around it. First, you yank a rope to pour the water, then kick the bellows to heat it. Then you move the ladder around and kick a valve to pour the boiling water into the infuser, where you add a tea ball and other ingredients before finally kicking another valve. Then, place a cup and pull another rope to pour the tea. Easy. And….calming. You always come back to the simple act of making tea, and even while the customers’ requests are more complex, it remains relaxing. Almost meditative. In real life, there’s something calming about making a cup of tea, and Wanderstop captures it perfectly.

Gathering up ingredients for tea is the other major gameplay element, and is quite straightforward. Tea leaves are harvested from around the clearing before being tossed into a dryer. That leaves the various fruits needed to flavour the tea, which brings us to a spot of gardening. Seeds are planted using a grid system, with a line of seeds making simple hybrid plants, and triangular designs creating the large hybrids that produce fruit. Easy.

Handing over a mug of tea to a customer is really just the method by which to trigger the next piece of story. What I find most intriguing is that you rarely get a customer’s full story, rather you typically get a snippet of their life, a momentary glimpse into their trials and tribulations. That’s because there’s a strong theme at play of being unable to magically fix problems. As the customers troop in and inevitably out of Alta’s life, she can influence them a little, perhaps guide them in a direction or just offer them a moment of respite, but she can’t fix them. Not really. The same goes for Alta, and I appreciate that sense of realism – she can learn to exist and breath and just be for a while, but when she eventually leaves she’ll still have to deal with her problems properly. There are no magic fixes, just hard work. And probably more tea.

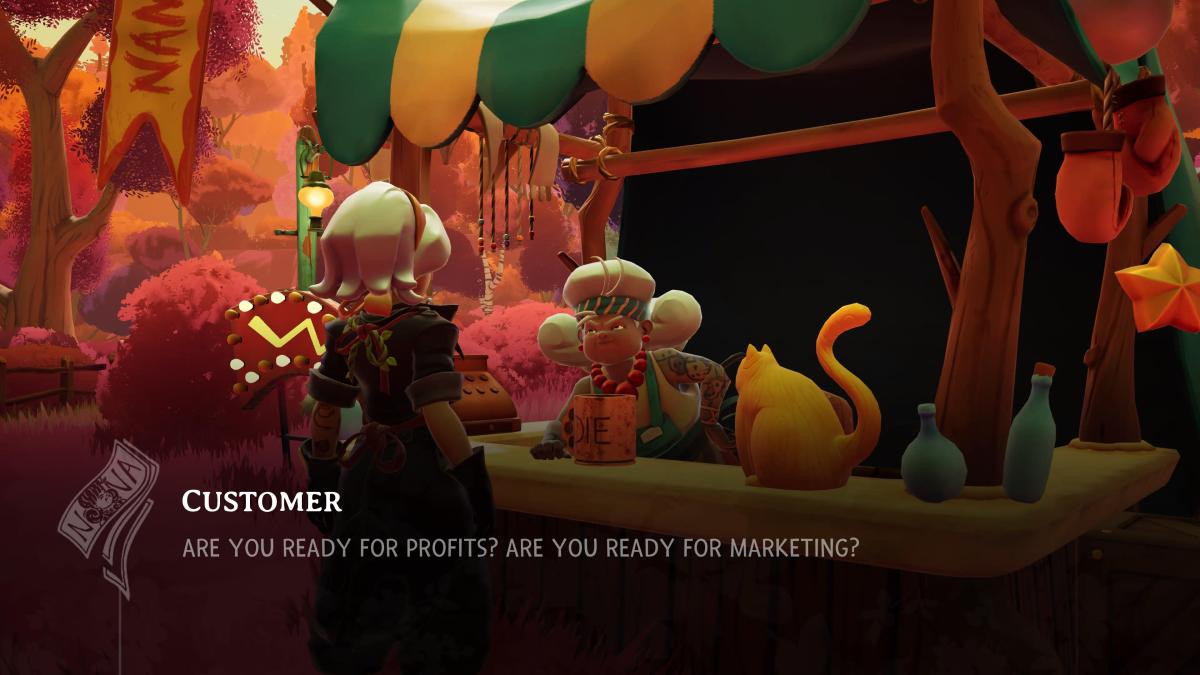

Going back to the customers for a minute, they are a varied and weird bunch, from numerous businessmen craving coffee and obsessed with delivering a presentation (and being followed around by a cosmic being who finds them fascinating), to the eager knight and his compulsive desire for his son to see him as cool. Some hang around for a while – like the grumpy Nana – while others are fleeting visitors. Eventually, they’ll go silent and stop talking to Alta, indicating it’s time to visit the shrine and move to the next “chapter” of the game. Those are sad moments, ones where I found myself not wanting my pals to vanish because the writing had endeared me to them.

There’s an interesting tension at the heart of Wanderstop. It wants to be a meditative experience about simply existing, about not always having to do something, and yet it’s still a game – and games, by their nature, demand action. You still have to brew tea, plant seeds, serve customers, and move forward. Given that this comes from the mind behind The Stanley Parable, that friction feels deliberate. The game can’t escape being a game, and that becomes part of what it’s saying.

Even the way the game handles its Achievements/Trophies is different, opting to dole that out on a timer rather than because you did anything specific. In fact, you could just sit around on a bench and eventually unlock them all, as far as I can tell.

In Conclusion…

Wonderfully warm and endearing, Wanderstop managed to do something a lot of games never do: bring out emotions in me. Although I’ve never had that obsessive drive to do one thing and one thing only, I do have trouble relaxing without feeling immensely guilty. Of course, the stupidity of the situation is when I fall into my own little mental pit, I don’t want to do anything at all. And then I feel guilty about it.

That’s beside the point, though. Wanderstop is a fantastic little game, a thoughtful adventure that isn’t afraid to tackle difficult ideas while dressing them up as something warm and inviting. Mechanically, it’s not the richest cuppa you’ll ever have, but it has that unmistakable flavour that tells you it was made with care. It’s the kind of game that doesn’t just ask you to slow down – it quietly sits beside you until you finally do.